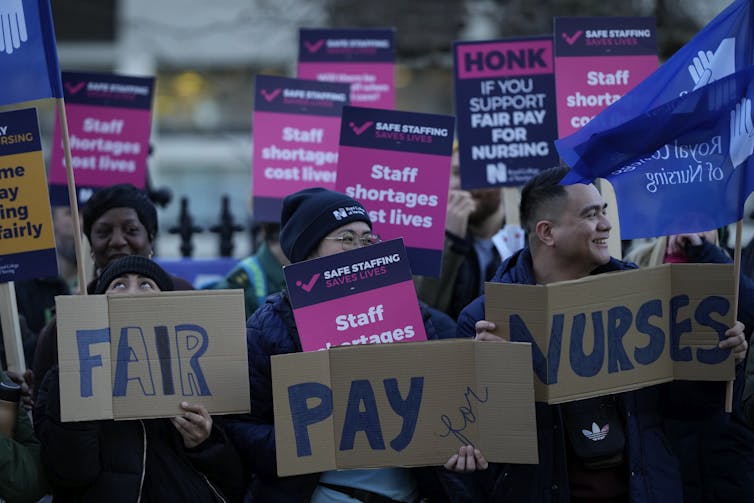

It is a “season of strikes” for health-care workers in the United Kingdom. Nurses and ambulance workers employed within the National Health Service (NHS) in England, Wales and Northern Ireland conducted the largest strike in the organization’s history on Feb. 6, 2023, after initiating strikes in December 2022.

Nurses, ambulance workers and physiotherapists will continue their industrial action this week. Junior doctors are set to follow after voting in favour of strike action this month.

Media attention to these labour disputes by Canadian and international news outlets has been intriguing. Health workers strike with regularity around the world, particularly in the COVID-19 era. Why, then, is there so much interest in these particular strikes?

Holding up a mirror

One reason is the context in which these strikes are occurring; the U.K. is facing labour disputes across multiple sectors, underscoring a broader and deeper crisis in government-labour relations in the country.

The global attention may also be affected by their unprecedented nature: U.K. nurses had never gone on strike in their century-long history as organized labour. Scale also plays a role, as strikes extended to a large part of the country.

But another reason motivating international interest might be that the strikes in the U.K. hold up a mirror to other parts of the world, including Canada, reflecting the discontent of our own health workers.

Read more: Patient aggression and physician burnout: The makings of a human resources crisis in health care

The labour concerns motivating this crisis — staffing shortages, pay, benefits, working conditions, repeated waves of COVID-19, burnout — are occurring around the world in different types of health-care systems. This suggests there is something fundamentally askew with health workforce policy globally. How, then, might the situation in the U.K. provide lessons about the health-care crisis unfolding in Canada?

Protests in Canada

In the U.K., health workers are demanding pay increases that account for inflation, as well as policies to address staffing shortages and underinvestment in the health-care system. These concerns bear conspicuous similarities to recent demonstrations from health workers across Canada.

Between 2021 and 2022, according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project database of protests and political violence, there were over 150 discrete demonstrations by Canadian health workers in every Canadian province.

Some of the higher profile events included protests against Bill 124 which would have limited pay increases in Ontario, protests against underinvestment and privatization of health services in Alberta, and the shortage of family physicians and nurses in British Columbia.

While the structure of Canadian health care might not result in a national protest similar to the ones in the U.K., the shared DNA across events in Canada is undeniable. These protests are clear manifestations of the deeper crisis in Canadian health care, fuelled by underinvestment, staffing shortages and attrition, burnout and repeated waves of COVID-19 and other respiratory illnesses.

These concerns echo demands from health workers around the world. An analysis of global health worker protests in the first year of the pandemic found that the vast majority of protests focused on remuneration and working conditions, such as insufficient or unpaid wages, risk allowances and job security. Clearly, health policy was not aligned with public declarations of health workers as heroes and warriors.

Short-term solutions don’t solve long-term problems

Many of the frustrations voiced by health workers in Canada, the U.K. and other countries predate the pandemic. Health workers have long drawn attention to problems of underinvestment and austerity through strikes and demonstrations.

Yet, health system leaders continue to address only the most immediate fires that need to be put out, rather than the underlying issues impacting health service availability and access. Not enough attention has been paid to the unintended consequences of using shorter-term solutions to address the workforce crisis.

For example, travel or contract employment have become a lucrative option for nurses in the United States and Canada frustrated with their working conditions and seeking more flexibility. But, hiring these nurses comes at a high cost to hospitals and creates lingering discontent in the workforce due to pay and benefits imbalances between travel nurses and staff nurses in the same facilities.

Recruiting nurses from low- and middle-income countries is another solution; yet, this approach results in labour shortages in low- and middle-income countries, where migration is an attractive option for skilled nurses due to workforce and system challenges in their own contexts.

The U.K. health worker protests echo problems here in Canada and elsewhere. More importantly, they are a harbinger of forthcoming labour disputes and systemic collapse if our health systems continue to be characterized by austerity, underinvestment and neglect of health worker voices.

Reform is urgently needed to address these challenges in a manner that pays heed to workers’ concerns, looks long term at workforce planning (and its consequences) and prioritizes sustainable investment in health systems. The costs of not seriously engaging with this type of reform are clear for all to see, across the pond.