Healthy Outrage is an apt title for a story that describes the journey Dr Trudy Thomas travelled during the various stages of her life. Thomas was the pioneer of community health programmes in South Africa. Her work spanned more than half a century, stretching through the dark years of apartheid and into the democratic era when she was asked to run the department of health in the Eastern Cape province after the 1994 elections.

Thomas entered the public health arena at a time when health services were heavily skewed towards white people under the apartheid government. This meant that resources were disproportionately allocated by the state and the vast majority of black South Africans received poor quality and inferior services.

In 1994 the dawn of democracy brought the constitutional promise of healthcare for all. But the optimism of the time was soon to wear thin: for Thomas too. Even before the new government’s first term was up, she had begun to express her disdain at the deterioration of healthcare.

And two decades later the public health care system remains in shambles. In the Eastern Cape, the health care system has collapsed. A report released by the human rights lobby group Section 27 revealed severe doctor shortages, a lack of ambulances and hospitals without water or essential equipment. Thomas contributed to the report when it was researched.

In Healthy Outrage, she describes how many of her experiences, particularly as a doctor dealing largely with children, provoked outrage. But her response was a “healthy” and constructive one. When faced with a problem she would sum up the key issues and then to go about addressing them, often with very limited resources.

The book is well written and is a fascinating read about one of the relatively unsung South African heroes of the past half-century. One of its main messages is how, with relatively few resources, a few people with integrity, commitment and hard work can achieve so much.

Her story

Thomas was born in 1936 and describes her early life of growing up in a working class family in Krugersdorp where her father was a miner on the gold mines. She excelled at school and went on to study medicine at the University of the Witwatersrand.

She soon struck up a relationship with Ian Harris. After they’d completed their studies they got married and went on to do their internships at what is now Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital in Johannesburg.

This proved to be a valuable preparation for the next phase of their lives as they learned practical skills in most areas of medicine. Thomas was struck by the enormous burden of preventable diseases that she saw in children, both infectious and nutrition related.

During this time the Sharpeville massacre took place and many of the injured were brought to Baragwanath Hospital where she was part of the team treating them. This had an important influence on her political outlook.

She and her husband moved to a remote health facility called St Matthews Mission in the Eastern Cape where they took over as the medical team. Thomas concentrated on the children’s ward; her training at Baragwanath Hospital stood her in good stead.

Serving the community

Thomas put enormous energy into travelling throughout the community providing primary health care.

She had very limited resources but used them to maximum effect with the full buy-in of the community. As she states in her book, this was community outreach long before the term was coined. It was only in 1978 that an International Conference on Primary Health Care in the Soviet Union led to the well known Declaration of Alma Ata which emphasised that effective primary care is fundamental to the health and well-being of any community. Thomas was well ahead of her time.

In 1974, the family moved to East London and it was here that Thomas’s political profile developed further. She got involved with the human rights organisation, the Black Sash, and also struck up a solid relationship with the charismatic black consciousness leader Steve Biko and his immediate family and associates.

I first met Thomas in 1976 while working at Cecilia Makiwane Hospital in what was then the Ciskei homeland. As a young doctor, I was enormously impressed with her clear views on how primary healthcare and community health complemented curative hospital care.

Thomas was put in charge of community health at the hospital and its 14 clinics. Despite her political opposition to the homeland policy she typically decided to make the most of the situation. For example, she coordinated an immunisation campaign that virtually eliminated measles in the region in the early 1980s, something the country hasn’t managed to achieve 35 years later.

At the helm

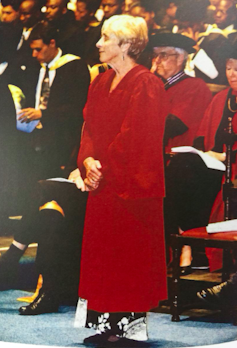

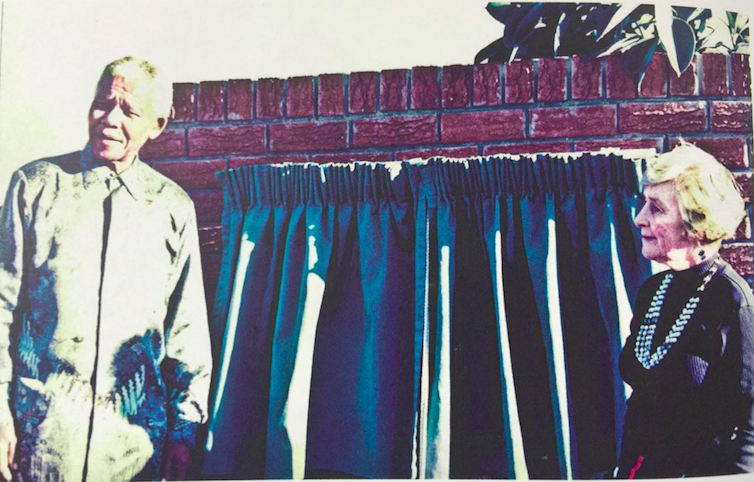

Thomas was full of hope and optimism when the first democratically elected government took over in 1994 and, somewhat to her surprise, was appointed to run the provincial health department in the Eastern Cape.

As one of the poorest provinces in the country, the challenge of developing an integrated and effective health system was enormous. She travelled the length and breadth of the province and achieved a great deal.

But her honesty and inability to toe the party line eventually led her into political disfavour and she was not appointed to a second term in 1999.

This didn’t stop her. She took up the fight against HIV and AIDS. She resigned from the African National Congress because of the government’s attitude to HIV and AIDS but continued to set up structures to assist and support AIDS orphans.